|

Diseases

|

BEAK OVERGROWTH AND DEFORMITIES

IN BUDGERIGARS AND PARROTS

Note for Pet Owners:

If your budgerigar or parrot develops overgrowth or deformity of the beak

take it to your veterinarian because there may be an underlying disease

present which needs to be diagnosed and treated with prescription medicines.

|

Description

The beak is usually kept in shape by

it's daily use in feeding and in assisting movement around the birds

environment. Overgrowth of the beak (usually the upper beak, but sometimes the

lower beak) and deformity of the beak are common disorders in pet Budgerigars

and Parrots

Cause

There are several possible causes :

- Inadequate activity, so inadequate

wear

- Malocclusion (the upper and lower

beaks do not meet properly)

- Infection with the mite

cnemidocoptes pilae (budgerigars and cockatiels)

- Inadequate nutrition (eg vitamin A or

D deficiency)

- A local cancer

- Liver disease

- Metabolic bone disease

- Psittacine beak and feather disease

syndrome or "beak rot" (cockatoos and other psittacines)

Breed Occurrence

All Budgerigars and psittacine birds can be affected

Signs

Obvious visible abnormalities of the beak or cere.

Complications

Abnormal beak conformations including beak

overgrowth can lead to difficulty eating, resulting in malnutrition or

starvation

Diagnosis

Examination of scrapings to identify mites, cytology or biopsy to confirm the

presence of a cancer, or other blood tests to confirm the presence of liver

disease.

Treatment

Whatever the cause of overgrowth or deformity the beak should be trimmed

regularly using small scissors and it can be filed down using a small nail file,

or sandpaper. This is to ensure that the bird can continue to eat normally.

Care is needed to avoid over-cutting as this will cause

bleeding. This can be stopped using a silver nitrate pencil - but often the bird

rubs it and bleeding starts again. For this reason beak trimming is best

performed by a veterinarian.

Moving the bird into a larger cage may help increase

exercise and so increase natural wear of the beak. Contrary to popular belief

cuttle bone and mineral blocks are not thought to help with beak growth.

The underlying cause (eg mites) should be treated

appropriately. See cnemidocoptes pilae.

Prognosis

The prognosis is good for mite treatment, but is poor for cancers. Once beak

deformity occurs regular management is usually needed.

Long term problems

Neglected cases may die from starvation and

general debilitation.

Causes of Death of Exhibition

Budgerigars

Dr John R. Baker

The

Liverpool University Budgerigar Ailment Research

Project, sponsored by the Lancashire, Cheshire and North Wales

including the Isle of Man Budgerigar Society, was started in 1984 and ran for

8 years.

In 1988-9 it was decided to find out

exactly what the causes of death of exhibition budgerigars are. All the birds

that died in the large studs of 3 fanciers in the year were post-mortemed. While

in some ways 2 of the studs were not typical, at least two of the findings were

of general interest. First in all three studs the average age of death was

around 2 years whereas the average age of death of pet birds submitted for

post-mortem examination is just over 6 years.

Why should this be so? It seemed

possible that exhibition birds were either more stressed with showing and

breeding than pets or that in breeding for exhibition features, stress

susceptibility had been bred into the birds. Microscopical examination of the

adrenals, the stress glands, did show marked differences between the pet and

exhibition bird but that raised the question as to which was normal, or if

either of them were.

After a year's work dealing with

Australian bureaucracy and getting a file 2½ thick of forms and correspondence,

I eventually managed to get adrenal glands from some wild budgies and it was a

surprise at first to find that they were similar to those of the exhibition

birds. Should this really have been a surprise? In retrospect I think not; life

expectation in the wild is probably less than 1 year and the birds are probably

stressed due to predators, and possible competition, in years when numbers are

high, for food and nest holes. The second thing to come out of this

cause-of-death survey was the importance of quarantine for new birds arriving at

a stud. In two of the three studs there were serious disease outbreaks following

the introduction of new birds which were mixed immediately with the others in

the flight. New birds should be quarantined well away from the resident birds

for at least three weeks. During this time disease may develop, the birds can be

tested to see if they are carrying disease or they can be given preventative

treatment.

Original text Copyright © 1989, Dr John

R Baker.

Clagged Vents

Dr John R. Baker

The

Liverpool University Budgerigar Ailment Research

Project, sponsored by the Lancashire, Cheshire and North Wales

including the Isle of Man Budgerigar Society, was started in 1984 and ran for

8 years.

In 1990-1 it was decided that we would

investigate the condition of clagged vents in which large amounts of droppings

accumulate around the vent and eventually block it and the bird then dies of an

accumulation of waste products in the body. Unfortunately on this occasion the

fancy let the research project down and the number of samples provided meant

that only provisional results could be obtained.

While several causes of the condition

were found it was predominantly due either to kidney disease or to

malfunctioning of the lower part of the bowel. As yet nothing can be done for

the former, which frequently rights itself if the vent is kept clear of

obstructions. In some circumstances the latter is treatable.

Original text Copyright © 1991, Dr John

R Baker.

Diarrhoea in Budgerigars

Dr John R. Baker

The

Liverpool University Budgerigar Ailment Research

Project, sponsored by the Lancashire, Cheshire and North Wales

including the Isle of Man Budgerigar Society, was started in 1984 and ran for

8 years.

After this success with a disease at the

top end of the digestive system (vomiting

budgies), in 1986-7 attention was turned to the other end to look at

why some birds developed diarrhoea. In some ways this was a less successful

investigation, in as much as it did not come up with as neat an answer as the

first two. Over 20 different causes of diarrhoea were discovered but none was

much more common than the others. Some of the causes were within the digestive

system itself; some outside it; some of the conditions were

treatable and others were not.

One of the commoner causes of the

disease was loss of the bacteria which should be present in the intestine. At

the end of the work, all we could do was suggest to the fancy that in cases of

diarrhoea if simple remedies such as cold tea do not work and the problem

persists, laboratory investigation of both the bird and samples of droppings is

essential to find the cause. In many cases antibiotics are not the answer to the

problem. If they are used, and in cases where the gut flora has been lost,

probiotics have a very useful role to play in restoring the germs which should

be present.

Original text copyright © 1987, Dr John

R Baker

DISEASES TRANSMITTED TO

EGGS

by Margaret A. Wissman, DVM, DABVP, Avian Practice

Early embryonic death, blood-ring, dead-in-shell.., these

terms frustrate and confound aviculturists, novice and professional alike. The

reasons that embryos die are many, and diagnosing the specific cause of death

can prove elusive in some cases. The serious aviculturist, whether a hobbyist or

one who makes her living from bird breeding, should work with an experienced

avian veterinarian who can help with all facets of aviculture. Every egg that

dies prior to hatching should be examined by an avian veterinarian who can

perform an egg necropsy and any other tests to determine the cause of death.

Often, histopathology (microscopic examination of tissues)

will prove diagnostic, if the embryo has recently died. Bacterial and fungal

cultures, stains of egg membranes, viral isolation and DNA PCR probes for

specific organisms may also help in diagnosing the cause of death. There are

many infectious organisms that can be transferred from the hen to the egg that

may cause the egg to die. In some cases, the infectious organism may infect the

egg, yet the embryo may continue developing, and may even hatch, carrying the

organism at hatch time. If an organism is passed from an infected hen directly

into an egg, and then into the developing embryo, this is called vertical

transmission. The term vertical transmission also describes the transmission of

an infectious agent from a parent to an egg during fertilization, during egg

development in the oviduct of the hen, or immediately after oviposition. Once

the egg is laid, some infectious organisms can pass through the eggshell upon

contact with contaminated feces, urates or bedding. This is also considered

vertical transmission if infection occurs immediately after laying. Some

organisms are transmitted from the ovary to the egg, and this is called

transovarian transmission. Infectious organisms harbored in the oviduct can also

be passed into the egg prior to the shell being formed. Some organisms infect

eggs if contents from the cloaca contaminate the surface of the egg, and then

penetrate the egg. The other method of transmitting infectious organisms is by

horizontal transmission. Horizontal transmission can occur by preening,

inhalation, copulation, insect or animal bites, ingestion, contact with

contaminated equipment or fighting. It seems obvious that prior to the egg

membranes and shell being applied to it, the egg would be susceptible to

infection by numerous infectious organisms. Even though the eggshell appears

solid, it contains microscopic pores that can allow liquids and small organisms

into the egg. The pores allow the transfer of gasses, as well.

Bacterial Diseases

Chlamydia psittaci is a primitive bacteria that can be vertically transmitted

from an infected hen through the egg to the embryo. Depending on the

pathogenicity of the strain and the number of organisms that are passed into the

egg, the embryo may die during incubation, or it may actually hatch as a baby

bird with chlamydiosis. It should be noted that transovarian transmission of

chlamydiosis has not yet been confirmed by researchers, so it may be that the

eggs are contaminated with the organism by some other vertical method. One

avicultural client of mine with over 100 pairs of large psittacines was having a

problem with a pair of blue-and-gold macaws. They pulled all of the pair's eggs

for artificial incubation. Several eggs in the incubator died about halfway

through incubation. During the egg necropsies, I tested for chlamydiosis by

sending in a swab for DNA PCR testing. I also tested the adult breeder pair for

Chlamydia, using the University of Georgia tests, which included DNA PCR testing

of the blood and DNA PCR testing of a choanal and cloacal swab. A latex

agglutination titer, was run through the University of Miami as well. The eggs

were positive for Chlamydia, as were the parent birds. I recommended that the

breeders remove from the incubator those eggs from the blue & golds, and isolate

them in a small incubator. There were five remaining eggs that were in the early

stages of incubation. To increase hatchability of the potentially infected eggs,

we began a course of egg injections, using injectable doxycycline, which is an

excellent drug for chlamydiosis. The eggs, much to our surprise, continued to

develop, and all five actually hatched on schedule. As soon as the eggs hatched,

I instructed the owners to begin medicating the hatchlings with oral doxycycline,

which would be continued for 45 days total. Because all baby birds receiving

antibiotic therapy should also be prescribed antifungal medication to prevent

infection with Candida sp., we also started the babies on a combination of oral

nystatin suspension and fluconizole.

The babies were also prescribed avian lactobacillus and

acidophilus to give them some normal, good bacterial flora. The five baby blue &

gold’s all developed normally and weaned on schedule. Subsequent testing showed

that these babies showed no signs of chlamydiosis. It should be noted that

testing is not always 100 percent accurate, and although treatment is often

curative, some birds may never completely clear the organism from their system,

resulting in asymptomatic carriers. However, these macaws have thrived and all

have remained healthy. Bacteria of the genus Salmonella can also cause embryos

to die in the shell, or, if the egg is contaminated by a very small number of

bacteria, Salmonella can cause weak-hatch babies that may die shortly after

breaking out of the egg. The bacteria may cause yolk material to coagulate in

the egg, dead embryos may show hemorrhagic streaks on the liver, and the spleen

and kidneys may be congested.

Pinpoint areas of the liver may be necrotic. Inflammation

of the pericardium may also be seen. Salmonella are motile bacteria that can

penetrate the eggshell and are transmitted vertically. Culture of the infected

embryo will prove diagnostic. Some Staphylococcus bacteria can kill embryos. The

avian embryo can be resistant to some strains of staphylococci, but can be

highly susceptible to other strains. Infected wounds on parent birds can infect

eggs, as can staph infections found on the hands of aviculturists, if the egg

comes in contact with lesions. Artificial incubators will grow staph readily,

and it can spread horizontally in this manner. An embryo can die within 48 hours

of exposure to some strains of staph, especially Staph, Aureus. The older the

embryo is at the time of the first exposure to staph, the less chance of

embryonic mortality. Hemorrhages may be found on various internal organs. A

laying hen can develop an ovary infected with Staph, Faecalis, which can

contaminate the forming egg. Contaminated eggs will have up to 50 percent

mortality. Culturing the egg is important for diagnosis. E. coil is a common

bacteria normally found in the gastrointestinal (Gl) tract of mammals, and some

birds as well.

It can enter the egg from an infected reproductive tract

of a hen. E. coil can also penetrate the eggshell if the egg is contaminated

with fecal material. E. coli commonly produces yolk sac infection, causing the

yolk sac contents to appear a watery yellow-green or yellow-brown. Dirty nests

and cages serve as sources of egg contamination. The use of water bottles may

reduce the amount of E. coil that builds up in the Gl tract of birds. In my

experience, aviaries that use a watering system, as opposed to water bowls, have

fewer problems with subclinical bacterial infections in their breeder birds and

their off-spring, Many embryos infected with E. coil die late in incubation or

shortly after hatching. If an E. coil infection is acquired during incubation,

the hatchling may develop an umbilical and yolk sac infection (omphalitis) and

may have poor weight gain. Cracked eggs are more easily infected and may serve

as a source of infection for other eggs in the incubator. Cracked eggs should be

repaired as soon as the damage is discovered, or they should be discarded.

Mycoplasma

Mycoplamatales are one order of microscopic organisms that replicate by binary

fission. They have no cell wall, but have a three-layer membrane. They are more

primitive than bacteria, and must live and grow inside the host. They live only

for a short time. Although we have much to learn about mycoplasmas, they can be

involved in problems with Cockatiel conjunctivitis and respiratory infections,

as well as respiratory/eye problems in other species of pet and breeder birds.

The organism is spread by the respiratory excretions and by the gonads of both

sexes, and infection in the air sacs may lead to contact transmission of the

ovary and developing follicle. Transovarian transmission can occur. Mycoplasma

can spread to the egg from an infected oviduct or from the semen of infected

male birds. It is possible to treat eggs infected with Mycoplasma infections.

Tylosin is injected into the air cell at the start of incubation. A combination

of lincomycin and spectinomycin is also effective for egg injection. Dipping the

eggs in antibiotic solutions reduces the incidence of disease; however, I

personally, have never used this method. A third treatment that has been useful

in breaking the transmission cycle of Mycoplasma gallisepicum and M. synoviae

involves elevating the temperature in a forced-air incubator to 46 degrees

Celsius for 12 to 14 hours before incubating the eggs normally. This technique

inactivates the Mycoplasma organisms, but it will reduce the hatchability by 8

to 12 percent.

Viral Diseases

Several important viral diseases are vertically transmitted in birds. Psittacine

beak and feather disease (PBFD) has been demonstrated to be vertically

transmitted, since the virus is found in the blood of infected birds. It has

been shown that artificially incubated baby birds from PBFD-infected hens will

consistently develop PBFD. So, attempting to control PBFD by pulling eggs for

artificial incubation is futile. Avian paramyxovirus 1 (Newcastle's Disease or

PMV 1) is one of a group of nine distinct serovars (with several more yet to be

characterized) of the virus that is dangerous to birds. Although paramyxovirus

is theoretically vertically transmissible, this mode of transmission is

considered unlikely because infected hens will generally stop laying eggs when

they are viremic. Eggs contaminated by virus-laden feces immediately after

laying can contaminate an incubator, and serve as a source of virus for recently

hatched neonates. Herpesviruses, most of which are quite species-specific,

include Pacheco's disease virus, Amazon tracheitis virus, respiratory disease in

Neophema sp. and Psittacula sp., wart-like or flat plaque-like lesions on the

skin of psittacine birds, budgerigar herpesvirus, pigeon herpesvirus (infectious

to budgies and cockatiels), falcon herpesvirus (infectious to budgies and Amazon

parrots), and Marek's disease (suggestive lesions in budgies). It has been

theorized that some hens latently infected with Pacheco's disease can pass the

virus (and antibodies to the virus) to their eggs. The resulting neonates would

be latently infected carriers that might not develop detectable levels of

antibodies. Herpesvirus of European budgerigars causes feather abnormalities

(referred to as "feather dusters") and is thought to be egg transmitted. It has

been demonstrated in dead-in-shell embryos and is considered a major cause of

early embryonic death in affected flocks, resulting in decreased egg

hatchability. Proventricular Dilatation Disease (PDD) is an enigmatic disease

that is being diagnosed with increased frequency. Although we have much to learn

about this disease, my personal experience indicates that PDD may be vertically

transmitted. I am working with an aviary that has a pair of severe macaws whose

eggs were taken for artificial incubation because the parents often damaged the

eggs after they were laid.

The eggs were placed in a new incubator, and the babies

were the only ones in the nursery during hand-feeding. The owner had problems

with the babies from day one, as the crops were slow to empty, and they did not

gain weight properly. The babies had to be given antibiotics, anti-fungals and

motility enhancers (cisapride) to get them to digest their food at all. One baby

died at six weeks of age, and histopathology showed all the classic PDD lesions.

The second baby died shortly after weaning, and, once again, histopath confirmed

PDD. Histopathological examination of tissues from a dead bird (especially the

proventriculus, ventriculus, crop, small intestines, and brain) is the only way

to confirm PDD in a dead bird as, grossly, many diseases can look like PDD. Dr.

Branson Ritchie at the University of Georgia is currently developing PDD tests,

and when they are available, we hope to test the parent birds of these two

babies. At this time, barium radiographs may render a presumptive diagnosis, and

the biopsy of areas of the gastrointestinal tract may prove diagnostic if

positive. Once the new testing becomes available, it will be easier to screen

for this terrible disease. Some adenoviruses, REO viruses and

reticuloendotheliosis viruses can be vertically transmitted. Influenza A may be

vertically transmitted, as well.

Parasites

Oddly enough, some parasites have been documented to occur within eggs. Adult

ascarids (roundworms) have been found within eggs. These worms get into the egg

by moving from the cloaca up into the oviduct, where the eggshell is then formed

around the aberrant parasite. The fluke, Prosthogonimus ovatus can be found in

the oviduct of Galliformes and Anseriformes, and may also be trapped within an

egg, but the flukes are more likely to result in abnormal eggshell formation.

Conclusions

As our knowledge of avian medicine and theriogenology grows, we may discover

other organisms that can be vertically transmitted. With the information that is

available today, it may be possible to save some eggs that have acquired an

infectious agent. Egg injections are routinely performed in my practice, and

this has greatly increased the hatchability of infected eggs. By testing for

infectious organisms, it is possible to cull eggs, as in the case of PBFD

persistently infected birds, or treat the parents, as in the case of many

bacterial or chlamydial infections. The result is healthier baby birds.

Margaret A. Wissman, DVM, Dip., ABVP-Avian Practise Dr.

Wissman and her husband, Bill Parsons, own and operate Icarus Mobile Veterinary

Service and Small World Zoological Gardens in the Tampa, Florida, area.

Dr. Wissman is a frequent author and lecturer.

French Moult in

Budgerigars - A Review

By: Inte Onsman, Research coordinator

MUTAVI

Research & Advice Group, The

Netherlands

As long as people

breed Budgerigars, French Moult has been the subject of many publications and

discussions. One of the first important publications about this feather disease,

was presented in Diseases of Budgerigars published in august 1951,

Wisconsin USA. At that time French Moult was believed to be caused by faulty

diet, overbreeding, and other factors and even a hereditary form was presumed.

The term "French Moult" was coined in Europe in the last century where the

disease was very prevalent in the 1870's. It had, however been known before that

time. The disease has been called French Moult because budgerigars which were

shipped all over Europe from the large breeding establishments in southern

France, either had the disease in its obvious form or carried it in its hidden

form. These birds when bred, would frequently produce a certain percentage of

youngsters suffering from French Moult. Two manifestations of F.M. were reported

then. The severest form is when young budgerigars in the nest never grow normal

feathers. They have been called runners, creepers, crawlers, or bullets. The

second, milder form of F.M. includes birds which may eventually grow a normal

coat of feathers and become good flyers.

Literature

As early as 1888

Dr. Karl Russ made a summary of statements by breeders on the subject of F.M. as

they had appeared in early bird journals. Dr. Russ, who was familiar with

microscopic work, did not ascribe the cause of F.M. to feather parasites, but to

faulty feeding, overbreeding, and breeding in rooms which are too warm. But the

most comprehensive study on F.M. has been done in 1932 by Dr. Hans Steiner from

the University of Zurich in Switzerland. By continuously inbreeding victims of

F.M. he was able to establish a strain in which this disease was carried on in

the "hereditary" form from generation to generation according to the Mendelian

Law. Dr. Steiner concluded from his experiments that F.M. is the result of

degeneration. The view that mites may cause F.M. has been mentioned many times

during the last 50 years or more, but has been abandoned each time.

In 1950 scientific

work on young Budgerigars suffering from F.M. was done by the Armed Forces

Institute of Pathology, Registry of Vetrinary Pathology, Washington, D.C. The

report published in All-Pets Magazine in May 1950, was very clear. F.M. is not

caused by parasites (including mites) nor by any other "bugs". To find an answer

to the question what really causes this unpredictable disease, more scientific

work was necessary. However, it was not until 1969 that T.G.Taylor published

some experimental investigations on F.M. in Diseases of Cage and Aviary

Birds. He came up with a definition and a describtion of the symptoms and

stated that the latter vary considerably and depend a great deal on the severety

of the attack. He also stated that these variable symptoms have led some people

to suggest that F.M. is not a single disease but that it includes several

distinct, though related, feather diseases. One of the most interesting findings

during these investigations was that a striking difference was found between

bone marrow smears obtained from healthy birds and birds suffering from F.M. Red

blood cells of diseased birds were abnormally fragile and the life span of the

erythrocytes (white blood cells) is unusually short. Taylor concluded, after

testing most theories, that the possibility that F.M. may be due to a virus or a

virus-like agent, should be taken seriously. However, it was not before 1981 the

first serious case report was published in Avian Diseases by Davis and

coworkers [5]. They reported high rates of mortality amongst fledgeling

budgerigars from aviaries in Georgia and Texas. Affected birds died acutely and

exhibited abdomal distention and reddening of the skin. Post mortem they found

enlarged heart and liver with areas of necrosis, and swollen, congested kidneys.

They examined a variety of tissues and found cells with enlarged nuclei

containing inclusions. Electron micrographs revealed the presence of viral

particles in the nuclei in the kidneys, feather follicles, liver, heart, bone

marrow, spleen and brain. Later on in a separate publication also in Avian

Diseases (1981), Bozeman and coworkers isolated a virus that belongs to the

Papovaviridae family [4]. They found characteristics that suggest the virus

belongs to this family, e.g. the presence of DNA, the side of viral replication

appearing to be in the nucleus, and the size of the virus particles ranging from

42 to 49 nm in diameter. (The name Papovavirus was chosen to denote papilloma

(PA), polyoma (PO) and vacuolating (VA) viruses). However,

they referred to the condition of affected birds as budgerigar fledgling disease

(BFD) and characterized a virus (BFDV) isolated from diseased birds.

Again in 1981

another research note was published in Avian Diseases by Bernier, Morin

and Marsolais from Canada [2]. They also reported high mortality rates in

Budgerigars between one and 15 days of age in 19 aviaries in the Province of

Quebec. Signs in adult birds were similar to those described as French Moult.

They considered F.M. to be a milder form of the infection described. Surviving

birds exhibited a retarded growth of flight and tail feathers. Results of their

investigations suggest that this disease of budgerigars is caused by a papova-like

agent that can replicate in many tissues of the body, causing widespread lesions

responsible for the high mortality rate in very young birds.

In 1982 Dykstra

and Bozeman published the results of a light and electron microscopic

examination of a "newly" described avian virus in Budgerigars [8]. They found

that the virus particles are of the same size and symmetry as members of the

polyoma subgroup of the Papovaviridae. The means of transmission of the virus

within an aviary population is less clear, though their studies have implicated

several possible routes. Adults may pass the virus by feeding their young by

regurgitation. Air currents circulating inside affected aviaries may also be

responsible for transmission. They also suggest a possible respiratory route of

transmission since virions within cells of lung tissue were found.

In 1984

Prof.Dr.Kaleta from Germany and coworkers, published some results obtained by

their investigations on young budgerigars showing signs of F.M. [13]. The birds

were purchased from five different sources. Infected cells were isolated and

examined electronmicroscopically. During this investigation intranuclear virus

particles were found with a diameter of 35-45nm.

In the American

Journal of Veterinary Research Dykstra and coworkers published a report to

characterize a virus linked to Budgerigar Fledgling Disease (BFD) which

previously had been identified as a papovavirus [9]. The purpose of this

investigation was to prepare further genetic investigations to develop a

possible vaccine as has been done for e.g. foot-and-mouth disease of cattle.

Their results showed little similarity to simian virus 40 (SV40) or polyomavirus

DNA. During the same year Bernier, Morin and Marsolais published an article in

The Canadian Veterinary Journal involving clinical and pathological

findings in budgerigars suffering from a papovavirus infection [3]. They

described one to 15 day old birds displaying a lack of nestling down feathers

and filoplumes on the head and neck. Microscopic lesions in the feather

follicles of the affected birds less than 15 days of age, were characterized by

focal, multifocal or diffuse ballooning degeneration in the plate cells of the

barb ridges. Again microscopic examination of these cells showed virus particles

similar to those already described by earlier investigators. Results of this

investigation suggested that a papovavirus can cause temporary absence, retarded

growth and the incomplete development of feathers in young budgerigars. The

infection was also suspected to be egg transmitted. The fact that eggs from

pairs producing affected young will also give diseased birds when fostered by

pairs whose own youngsters are normal, supports the hypothesis of

egg-transmission. It was suggested that F.M. is a nonfatal form of the

papovavirus infections described in budgerigars.

Lynch and

coworkers from the Veterinary Laboratory Services Branch, Ontario, Canada, also

published their results in Avian Diseases (1984)[18]. They examined birds

from three unrelated outbreaks of disease occurring in Ontario in 1981,1983, and

1984. Egg-inoculation experiments suggested that the disease may be

egg-transmitted and that significant virus replication must occur before the

budgerigar's immune system matures sufficiently to mount a response.

In the year 1984

many research was carried out on this unpredictable disease. Jacobson and

coworkers reported 45 fledling psittacine birds being raised in an avian nursery

of which 14 died over a 6-week period [12]. Birds died acutely with full crops,

abdominal distention, and hemorrhagic skin. Feather abnormalities were seen in

birds older than 15 days. In this report, a die-off of fledgling conures and

macaws was described. Electron microscopy demonstrated a virus similar in size

and conformation to BFDV (Budgerigar Fledgling Disease Virus).

They concluded that the psittacine papovavirus present in affected birds,

appeared to be related to the polyomavirus subgroup of the papovaviruses. They

also concluded that fledglings from seronegative parents should not be

introduced into a nursery with chicks from seropositive parents. Also in the

same year Pass and Perry from the School of Veterinary Studies, Murdoch

University, Murdoch, Western Australia, described a disease called Psittacine

beak and feather disease [21]. The disease is characterized by loss of feathers,

abnormally shaped feathers and overgrowth and irregularity of the surface of the

beak. The disease was seen in Sulphur-crested Cockatoos, Lovebirds, Budgerigars

and Galahs. During their investigations they found viral particles 17 to 22 nm

in diameter who could be identified in a later state as the picorna virus which

is not a member of the Papova virus family.

In 1985 Pass

published a papova-like virus infection of Lovebirds [22]. The article was

published in the Australian Veterinary Journal and contained information

about similarities to papovavirus infections of psittacine birds described

elswhere.

Krautwald and

Kaleta (1984) investigated 250 budgerigars obtained from 45 different breeders.

Approximately 50 birds came from breeders who never had F.M. in their aviaries

[14]. It was observed that birds who never had any problems with F.M. were very

easy to infect for lack of sufficient antibodies. In the German Cancer Research

Center of the University of Giessen, Lehn and Müller (1986) cloned and

characterized for the first time a virus isolated from fledgling budgerigars,

designated BFDV [16]. A relationship to the polyomavirus subgroup was already

recognized and suggested by previous investigators, but it was now confirmed by

this investigation. Their experiments showed that BFDV is related to but not

identical to the other polyomaviruses. Until now, polyomaviruses had been

isolated only from a variety of mammalian species including man; in contrast,

BFDV represents the first avian member of this subgroup. Lehn and Müller found

strong evidence that BFDV is associated with French Moult.

In 1986 Müller and

Nitschke from the Institute for Virology, University of Giessen, Germany,

investigated a virus isolated from fledgling budgerigars suffering from F.M.

Results obtained by their investigation led to the conclusion that the virus

isolated warrant the classification as a polyoma-like virus [20].

David Graham and

Bruce Calnek reported in Avian Diseases (1987), a papovavirus infection

in 44 parrots of at least 18 species exclusive of the budgerigar [10]. They

compared this infection to a generalized virus infection of young budgerigars

which had been recognized in the United States, Canada, Italy, Hungary, Japan,

and the Federal Republic of Germany. A papovavirus infection was confirmed in 27

of the birds by using antibody tests.

In the Journal

of Veterinary Medicine (1989), Krautwald, Müller and Kaleta from the

Institute of Poultry Diseases and Institute of Virology, University of Giessen,

Germany, examined 298 budgerigars from 49 different flocks in order to obtain

some insight into the aetiology of FM and BFD [15]. The difference between birds

infected with FM and birds infected with BFD is that FM birds mostly survive and

BFD infected birds die when 2-to-3-weeks old. Mortality rates even reached up to

100% in several flocks. However, surviving budgerigars showed disorders of

feathers, similar to those of birds with FM; these birds remained less

developed, and many of them were unable to fly (runners). The structural and

physicochemical properties of viruses isolated from budgerigars with BFD and

from several budgerigars with FM described by Krautwald and coworkers and their

results published in a previous paper (1984) confirm the recently published

classification of BFDV as a member of the polyomavirus group (Lehn and

Müller,1986; Müller and Nitzschke,1986). They proposed to place this virus into

a distinct subgroup within the polyomavirus family.

Regine Stoll and

coworkers (1993) studied molecular and biological characteristics of avian

polyomaviruses from different species of birds including chickens and a parrot

[24]. The chicken polyomavirus is called BFDV-2 and the parrot polyomavirus is

called BFDV-3. The non-mammalian polyomavirus isolated from Budgerigars is now

called BFDV-1 virus. They consider Budgerigar Fledgeling Disease virus (BFDV) to

represent the first avian virus being recognized as a member of the polyomavirus

genus in the family papovaviridae (Müller & Nitschke, 1986;Lehn & Müller,1986).

They also consider French moult of Budgerigars to be a milder and more

protracted form of a BFDV infection resulting in chronic feathering disorders

(Krautwald,1989). It is proposed that the avian polyomaviruses should be placed

in a distinct subgroup within the polyomavirus genus of the family Papovaviridae

and the designation Avipolyomavirus is suggested (Stoll,1993).

The aetiology of

French Moult has been very well investigated throughout the years. It appeared

to be a contageous viral disease caused by a member of the papovaviridae family

and is designated now as the avipolyomavirus. This mammalian virus was obviously

able to adapt, replicate and survive in psittacine birds because of its unique

properties (Griffin,1983) [11]. Two forms of the disease have been recognized in

Budgerigars; the most severe form (BFD) causing mortality rates up to 100% in

budgerigar fledgelings and a mild form called French Moult causing feather

disturbances resulting in birds called "runners". If an outbreak of the disease

occurs, precausions should be taken to prevent the virus from spreading

throughout the aviary (Baker,1990) [1]. Adult birds probably spread the disease

through feather dust and droppings. Runners spread the virus through feather

dander, feather dust and droppings. The infection is egg-transmitted for eggs

from pairs producing affected young will also give diseased birds when fostered

by pairs whose own youngsters are normal. The use of an effective disinfectant

such as Vircon S is recommanded. If the disease is present in your aviary, do

not sell or exhibit birds because if you do so, you will spread the disease to

other fanciers.

Granulocytic Sarcoma in a

Budgerigar (Melopsittacus

undulatus)

AnaPatricia García, Kenneth S. Latimer, W. L. Steffens,

and Branson W. Ritchie

College of Veterinary Medicine, The University of Georgia,

Athens, Georgia 30602.

Abstract. An adult female

Budgerigar was presented with dyspnea and abdominal distention. After a few days

of supportive treatment the bird died and a necropsy was performed. A large,

cystic, perihepatic mass was present. Microscopically, this mass was composed of

multifocal to coalescing aggregates of proliferating heterophils. The neoplastic

cell population showed maturation from the blast stage to differentiated

granulocytes. Electron microscopy demonstrated that the granulocytic cells

belonged to the heterophilic lineage. The final diagnosis was granulocytic

sarcoma.

Key Words: Avian,

Budgerigar, Melopsittacus undulatus, Chloroma, Granulocytic

sarcoma, Heterophil, Myelocytoma, Myeloblastoma

Introduction

Granulocytic leukemia is the neoplastic proliferation of

granulocytes originating in the bone marrow. Infrequently, granulocytic leukemia

in mammals is associated with the formation of sarcomatous tissue masses called

chloromas.1 These neoplastic tissue masses usually arise in visceral

organs. They are characterized by a green color that is imparted by

myeloperoxidase in the specific (azurophilic) granules of neutrophils. Similar

hematopoietic neoplasms in birds are known by the synonyms granulocytic sarcoma,

myelocytoma, or myeloblastoma. These neoplasms are associated with the

proliferation of heterophils and their precursors, which lack myeloperoxidase.

Granulocytic sarcoma is relatively common in domestic fowls but is rare in

exotic birds.1-3 The purpose of this case report is to describe a

granulocytic sarcoma in a Budgerigar.

Case Report

An adult female Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus)

was presented to the University of Georgia Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital

with abdominal distention and dyspnea. The bird died a few days after admission

despite supportive treatment. Necropsy examination of the animal revealed a

large, cystic, perihepatic mass.

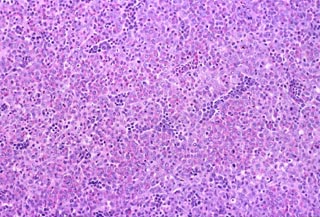

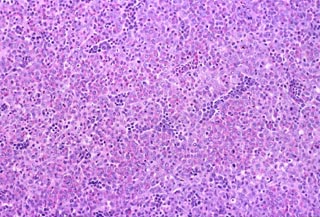

Microscopically, the mass was composed of multifocal to

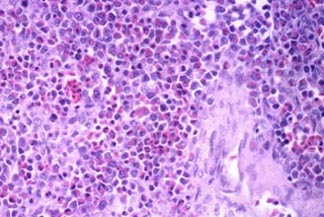

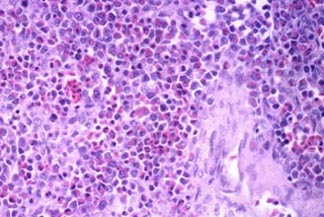

coalescing aggregates of proliferating granulocytes (Fig. 1). This cell

population showed maturation from myeloblasts to more differentiated

granulocytes (Fig. 2). Cytoplasmic granules appeared red and slightly elongate,

suggesting heterophilc cell lineage. The neoplasm also contained numerous

variably sized and shaped vascular spaces. More normal sections of liver

contained scattered foci of extramedullary heterophil production, often centered

around blood vessels beneath the hepatic capsule.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1.

Budgerigar, granulocytic sarcoma, H&E stain. Perihepatic mass appears

hypercellular. |

Fig. 2.

Budgerigar, granulocytic sarcoma, H&E stain. More differentiated cells

contain red cytoplasmic granules. |

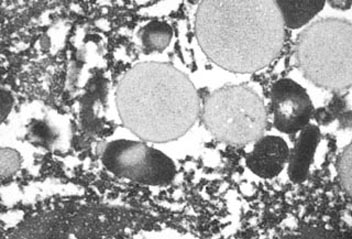

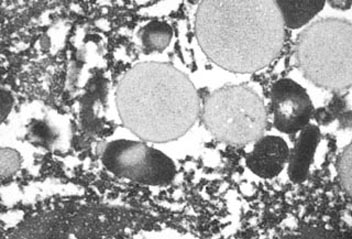

Electron microscopy of ultrathin sections of the mass

revealed two types of neoplastic cells. The first cell type consisted of large,

round blasts with a thin rim of cytoplasm containing occasional granules. The

second cell type appeared smaller, round , and more differentiated. These cells

had more aggregated chromatin within cell nuclei and more abundant cytoplasm

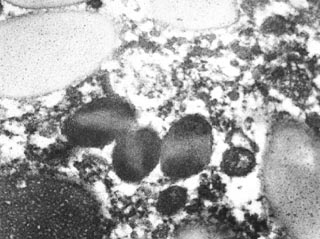

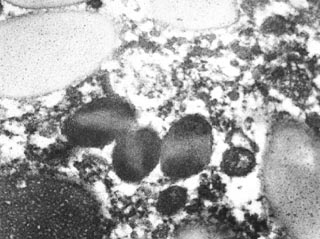

containing membrane-bound granules (Fig. 3). The cytoplasmic granules were round

in cross section and elongated in longitudinal section. Some of the granules

were more electron dense than others and occasionally appeared to have a lighter

central core (Fig. 4). These ultrastructural characteristics were typical of

heterophilic lineage. The definitive diagnosis in this Budgerigar was

perihepatic granulocytic sarcoma.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3.

Budgerigar, granulocytic sarcoma, electron micrograph. Heterophil

granules are round in cross section and elongate in oblique or

longitudinal section. Notice variation in granule radiodensity. |

Fig. 4.

Budgerigar, granulocytic sarcoma, electron micrograph. More radiodense

heterophil granules occasionally have a lighter central core. Radiolucent

granules also are present. |

Discussion

Neoplasia is a frequent cause of death in pet Budgerigars

(Melopsittacus undulatus), affecting more than 15% of birds that are

examined at necropsy.1 The most common neoplasms in Budgerigars are

carcinomas of the kidney, ovary, and testis. In contrast, hematopoietic

neoplasms are rare in Budgerigars. Carcinomas of the genitourinary tract and

fibrosarcomas in chickens are part of a spectrum of neoplasms that may be caused

by infectious type C retroviruses (avian leukosis/sarcoma viruses). In addition,

two similar forms of hematopoietic neoplasia (designated myelocytomatosis and

myeloblastosis) have been observed in chickens. These neoplastic diseases are

associated with avian myeloblastosis virus and often result in hepatomegaly and

splenomegaly from neoplastic cell infiltration.1 Furthermore,

myelocytomatosis is associated with the formation of neoplasms on the surface of

bones with intimate contact to the periosteum. These neoplasms consist of

compact masses of uniform myelocytes. In contrast, myeloblastosis affects most

parenchymatous organs and is characterized by massive intravascular and

extravascular accumulations of myeloblasts with a variable proportion of more

differentiated myelocytes.2

The avian leukosis/sarcoma viruses are closely related

and, depending on their genetic makeup, cause a variety of neoplasms with short

to long latencies. Some viral strains such as avian myeloblastosis virus, avian

erythroblastosis virus, and the sarcoma viruses contain specific viral oncogenes

that cause rapid neoplastic transformation of target cells with subsequent tumor

development within a few days or weeks. These avian leukosis/sarcoma viruses of

chickens have been divided into six subgroups (A, B, C, D, E and J) on the basis

of their host range in chicken embryo fibroblasts of different genetic types,

interference patterns with members of the same and different viral groups, and

type of viral envelope antigens. Viruses of subgroup A and B occur as common

exogenous viruses in the field. In contrast, viruses of subgroups C and D rarely

have been associated with field disease in chickens. The subgroup E viruses

include the ubiquitous endogenous leukosis viruses of low pathogenicity.2

Subgroup J viruses have been isolated from meat-type chickens and are associated

with an increased incidence of myelocytomatosis.2,3

In chickens and other animals harboring infectious

retroviruses, the virus particles can be detected readily by electron

microscopic examination of normal or neoplastic tissues. However, electron

microscopic search for retroviral particles

in budgerigar neoplasms has been unrewarding.4 Using immunodiagnostic

techniques, avian leukosis viral antigens have been detected in sera from

tumor-bearing Budgerigars using an enzyme-linked immunosorbant (ELISA) assay.5

In addition, renal tumor tissues from Budgerigars were positive for the RAV -2

strain of avian leukosis virus using dot-blot analysis and Southern blot

hybridization. These data suggest that avian retroviruses may be implicated as

etiologic agents of certain neoplasms in Budgerigars. In the Budgerigar of this

report, we did not observed viral particles in granulocytic sarcoma tissue

prepared for electron microscopic examination. Further analysis of neoplastic

tissue will be required to confirm or refute the presence of retroviruses in

this neoplasm.

Granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma, myelocytomatosis,

myeloblastic sarcoma, myelocytic sarcoma) has been reported in four Budgerigars

and a White-tailed Black Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus funereus latirostris).6

The histologic differential diagnosis for these lesions also includes osseous

metaplasia, extramedullary hematopoiesis, myelolipoma, and hemangiolipoma.7

Osseous metaplasia is recognized by the presence of osteoid and spicules of

mineralized bone associated with the hematopoietic cells. Extramedullary

hematopoiesis occurs with some frequency in birds and may be observed in diverse

locations including the spleen, liver, kidney, adrenal gland, gastrointestinal

tract, heart, and dura mater. Histologically, extramedullary hematopoiesis is

associated with the production of mature leukocytes, erythrocytes, and/or

thrombocytes in any combination. Hematopoietic cell proliferation is

unaccompanied by sarcomatous tissue masses. Myelolipoma consists of the

coproduction of hematopoietic cells and lipocytes. These masses are observed

most commonly in the subcutis and liver, but also may be observed within the

thoracoabdominal cavity.7,8 Hemangiolipoma consists of adipose tissue

and a vasoformative component similar to hemangioma. The diagnosis of

granulocytic sarcoma is based upon the presence of a sarcomatous tissue mass

composed of proliferating myeloblasts that show little differentiation to mature

granulocytes.

Diarrhoea in Budgerigars

An Approach to Treatment

Dr John R Baker

Diarrhoea, otherwise known as

scour, wet vent or, is a common complaint affecting either an individual bird or

the whole stud. Diarrhoea varies widely in appearance from normal colour but

soft or runny, to odd colours, mostly grey or grey-green. If dark, bottle-green,

soft droppings are being produced, this indicates that the bird is not eating

but there is probably nothing wrong with the bird's digestive system. If the

black part off the dropping is normal but the white part is soft or fluid, this

indicates kidney problems which are not covered by this article. As described

elsewhere, the causes of diarrhoea

are many and varied, and some of these are amenable to treatment and others are

not. The aim of this article is to give fanciers some help in the treatment of

affected birds always remembering however, that the best person to advise on

treatment is a veterinary surgeon with an interest in cage bird diseases.

The first thing to do, once you

have spotted that you have a bird with diarrhoea, is to catch it and have a

close look at it to check if there are any other symptoms. Is there any matting

of the feathers on the head indicating that the bird is vomiting as well? Look

at the bird's beak and eyes - do they look normal? If not, it may well not be a

digestive problem. Gently feel the bird behind the keel bone (sometimes known as

the breast bone which can be felt as a hard line along the lower side of the

birds chest) - is it pot-bellied or can you feel a swelling which should not be

there? This could indicate cancer which your veterinary surgeon might consider

attempting to operate on. If you notice these or any other symptoms, consult

your veterinary surgeon as soon as possible. For the purposes of this article we

will assume, apart from the diarrhoea, there is nothing else to be found other

than the bird being fluffed up and perhaps not eating.

Having examined the bird it

should not be put back in the flight where it might spread it's disease to other

birds, but put it in a cage on its own or with other similarly affected birds.

The next thing to do is to decide how the bird is. Is it bright and alert and

looking around at its new surroundings, or is it ill, as indicated by it being

dull, listless, fluffed up and sitting on the floor of the cage?

If the bird is obviously ill,

treatment is urgently required otherwise the bird will die. The first thing it

needs is warmth and it should be put somewhere where the temperature is about

80 Fahrenheit. Ideally, this should be in a proper hospital cage, but the use of

a show cage in the airing cupboard is quite a good idea if you don't have a

proper hospital cage. It will also need fluid; about a teaspoonful (6ml) a day

divided into 5 or 6 doses and also containing a readily digested source of

energy.

If you make up a solution of

2 heaped teaspoonfuls of glucose to 3 pints of water this will supply both

requirements. This should be given warm and directly into the crop with a dosing

tube, (available from good pet shops) which all fanciers should have in stock

and know how to use. If you have not used one before ask a local experienced

fancier or your veterinary surgeon how it is done. If the bird does not respond

to this treatment within a day or two the outlook is not good and it should be

seen by your veterinary surgeon.

If the bird shows little or no

sign of illness, except for the diarrhoea, and is eating and drinking, there is

a possibility that some change in management may have upset its insides. Has it

recently been purchased, been to a show, been introduced to a strange group of

birds, had its diet or water changed, or been given large amounts of green food?

If any of these has happened the chances are that the bird will get over its

problem in a day or two. Most of the birds we receive at the University for

examination have diarrhoea for the first day but nearly always get over it

quickly without treatment. If the problem persists, put the bird back on its old

diet and/or water or take it out of the strange group and see if this does the

trick. Another not uncommon cause of diarrhoea is stress; some birds can not

cope on their own and some can not cope with being mixed with others and, in

both these situations there can be an intestinal upset. If you find, for

example, that each time you put a specific bird in a flight it gets diarrhoea,

this will be one of these stress susceptible birds which are upset by being in

the flight. Remember that the large, bulky, wet droppings produced by breeding

hens are quite normal and should not be confused with diarrhoea.

If there has been no change in

the way you look after the birds and there is a problem with diarrhoea then you

will have to start to think about some form of treatment. The first point to

make about this is that the last thing you should use are antibiotics. Don't

dash for the yellow powder that most fanciers seem to have. The reasons for this

are first, that only very rarely is diarrhoea due to specific disease causing

bacteria which are the only thing which antibiotics will cure and second, the

more you use antibiotics the more likely they are to lose their effectiveness.

Antibiotics do have an important role to play in bird medicine but they are not

the first drug of choice for the treatment of most cases of diarrhoea. The way

to treat the bird is what is termed symptomatically that is, treating the

symptoms rather than a specific disease. What we need is something which will

calm the gut, and two things which are good for this are cold strong tea - about

a teaspoonful - and kaolin (pure kaolin from the chemists, don't use

preparations for treating humans which have other things added) about 1 or

2 drops. These should be given directly into the birds beak or better still with

a dosing tube.

If the diarrhoea persists other

treatments may be tried. The work we have done at the University suggests that

quite a number of cases of diarrhoea are due to a disturbance in the types and

numbers of bacteria in the gut, without a specific disease causing germ being

present. It is necessary in these cases to re-establish the normal germs. There

are two ways of doing this, one way is to collect some normal droppings from

healthy birds, make these into a slurry with a few drops of water and, with a

dosing tube put this into the birds crop. Obviously there is the risk of

spreading disease if this is done and a better approach is to use a probiotic.

These are available from the pet shop under a wide variety of trade names. One

that is normally available is called "Revive" but there are a number of others

which are equally good, on the market. Probiotics are cultures of harmless germs

which are normally present in the birds intestines and the idea is to swamp any

germs which might be causing the problem and re-establish the normal ones and

hopefully, cure the disease. They can also be used to establish germs in the

intestines when they have been lost for some reason. Some of these come with

their own dosing tube holding the right amount and with others the instructions

on the bottle should be followed

If none of these methods work

now is the time to try antibiotics if you have some in stock. If not, contact

your veterinary surgeon and show him the bird and he will probably prescribe

them. If the antibiotics don't cure the problem contact your veterinary surgeon

and ask him to arrange for samples of droppings to be sent off to a laboratory

for examination so that the specific cause of the problem can be identified and

the correct treatment given.

Megabacteria in Diseased and

Healthy Budgerigars

Dr John R Baker

Megabacteria are associated with disease

and death in Budgerigars and a range of other birds. They inhabit the

proventriculus or true stomach where they cause changes in the structure and

function of the organ. The proventriculus becomes dilated and the wall

thickened; the production of digestive juices is impaired; excess mucus is

produced and there may be ulceration at each junction of the proventriculus and

gizzard. The disease is extremely common in exhibition Budgerigars in the UK and

is the major cause of illness and death in these birds.

Megabacteria Carriers

It was believed that apparently healthy

birds could carry this infection and live in balance with it, and that these

birds were responsible for spreading the infection from stud to stud as birds

were bought, sold and exhibited. Some vets, and others, believe that

megabacteria are normal inhabitants of the bird's stomach, and that some other

disease is responsible for the changes in the proventriculus which allows the

number of megabacteria to increase. No proof of this has ever been produced so

work was carried out to establish whether carriers existed or not. Was

megabacteria after all, simply a normal inhabitant of the proventriculus? It was

also hoped that it would be possible to demonstrate the role of megabacteria in

causing proventricular disease.

Diagnostic Focus on Megabacteria

As part of the Budgerigar Society

diagnostic service, dead Budgerigars are examined post-mortem. In 160 birds

received over the last few months, particular attention has been paid to the

proventriculus, and this organ has been examined for megabacteria regardless of

the cause of death. The results were as in the table below.

|

Results of Diagnostic Focus |

|

|

With Megabacteria |

Number of birds |

% of birds in the group |

|

Birds with normal proventriculi |

Yes |

28 |

33 |

|

No |

57 |

67 |

|

Birds with abnormal proventriculi |

Yes |

69 |

92 |

|

No |

6 |

8 |

High

Numbers of Carriers

As only one-third of the birds with

normal proventriculi have megabacteria in the organ, the bacteria cannot be

considered to be a normal inhabitant of this part of the Budgerigar. However, in

most other diseases where clinically normal carriers are present, they form a

lower percentage of the population than this. A possible reason for the high

prevalence of clinically normal carriers, is the very high prevalence of the

clinical disease which results in large numbers of healthy birds being exposed

to the infection and becoming unwell or carriers of the infection.

Other

Causes of Abnormal Proventriculi

The birds with megabacteria infection of

an abnormal proventriculus showed changes, such as an excess of mucus in the

organ or a minor degree of dilation, thickening of the wall, and ulceration at

the junction of the gizzard and proventriculus. Many of these birds had been

clinically ill but, in some of the cases of birds with minor lesions, the birds

had died of other causes. While nearly all cases of abnormal proventriculi were

due to megabacteria infection, a few were not. In this survey six birds had

abnormal proventriculi due to:

- In two cases, E. coli

infection.

- In two cases, ulcers.

- In one case, a cyst.

- In one case, of excess mucus

production of an unknown cause.

Conclusions

For a small survey it can be seen that:

- Proventricular disease is almost

always due to megabacteria infection.

- That there are many clinically normal

carriers in the Budgerigar population which can go either up or down with the

infection when subjected to stress, or remain as carriers posing a risk to

un-infected birds they come into contact with.

- Megabacteria do not appear to be

normal inhabitants of the proventriculus of Budgerigars.

Original text Copyright © 1997, Dr John

R Baker.

Megabacteriosis:

Notes for Budgerigar Fanciers

Dr John R Baker

This is a copy of the notes that Dr

Baker sends out after carrying out post-mortem examinations.

Megabacteriosis is an infection of the

stomach which interferes with the proper digestion of the food, and in the long

term, the affected birds die of starvation. Some of the affected birds show

retching or vomiting and some have diarrhoea. Occasionally birds die rapidly

from this disease, and in these cases there has been the formation of an ulcers

in the stomachs and the birds can bleed to death internally from these.

There appear to be different strains of

this bacteria, some of which cause relatively rapid death, while others cause

mild symptoms which can last for a long periods, months, and occasionally years,

before the condition becomes serious.

Once this infection gets into a stud,

you must expect occasional birds to go down with this disease. This is

particularly prone to occur when the birds are subjected to stress, for example,

when they are put down to breed, taken to shows or moved to a new owner's

premises.

The disease is extremely common and the

majority of studs are affected.

There is a drug which will eliminate the

megabacteria from the birds, but only rather more than half the birds get better

because, in some birds, the damage to the stomach is so severe that it never

heals. To be effective it is essential to treat birds early on in the disease.

It may be worth getting some of the drug to try treatment of any other birds

which go down with weight-loss and the symptoms described above. The drug is

amphotericin B which is sold under the trade name of Fungilin Suspension

(manufactured by E R Squibb and Sons Ltd). Birds should be given 0.1 ml of this

preparation into the beak, or preferably by crop tube, twice a day for at

least 10 days. It is very important that there is no break in the treatment and

that the doses are given at 12-hour intervals. I regret that it is not possible

for me to treat affected birds here. You will be able to obtain the drug through

your local veterinary surgeon; you may have to show him this letter and some of

the birds before he will let you have it.

You may have read in the fancy press

that the condition can be treated with various acids; I have tried a number of

these completely without success

Unless you are prepared to dose all the

birds as detailed above, there is no way of eradicating the infection from a

stud with drugs available here. The Australians do have a drug which can be

given in the drinking water to eliminate this infection, but unfortunately, it

is not available in the UK. The immunity to this infection is weak, so that if

treated birds are exposed to the infection again, for example at a show, or if

an infected bird is bought and added to the stud, they are very likely to catch

it and the disease may reappear.

While I have use amphotericin B in a

very large number of birds without ill effect I am required to tell you that

the product is not licensed for use in birds. This means that if some

adverse reaction occurs you will have no claim on the manufacturers, the

veterinary surgeon prescribing the product, nor myself.

Original text Copyright © 1997, Dr John

R Baker.

Liverpool University

Budgerigar Ailment Research Project

Overview

Dr John R. Baker

The research

project into budgerigar ailments, sponsored by the Lancashire, Cheshire and

North Wales including the Isle of Man Budgerigar Society, was started in 1984

and lasted for 8 years. From 1992 there will be some change of emphasis so this

seems a good time to look back at what has been achieved.

The project starts

each year in February and prior to this discussions are held to decide the topic

for the year. The aim is to pick a topic of interest to the fancy, which stands

a reasonable chance of being completed in the year, and taking into account the

limited time that I can devote to research and the constraints imposed by the

finance available. The latter two are particularly important and mean that a

number of topics of great interest to the fancy, such as French moult, cannot be

investigated.

1984-5:

Going Light

The topic chosen for 1984-5 was 'going

light.' Many diseases of cage birds make them lose weight and 'go light.'

1985-6:

Vomiting Budgies

1985-6 was the year of vomiting budgies.

Birds actually being sick or or trying to vomit were noticed by a number of

fanciers as being a common problem.

1986-7:

Diarrhoea

After this success with a disease at the

top end of the digestive system, in 1986-7 attention was turned to the other end

to look at why some birds developed diarrhoea.

1987-88:

Reproduction

In 1987/88 attention was turned to

reproduction and in particular why exhibition budgies had (and still have) such

an abysmal breeding record when compared with almost all other breeds of cage

birds and poultry.

1988-89:

Causes of Death of Exhibition Budgerigars

In 1988-89 it was decided to find out

exactly what the causes of death of exhibition budgerigars are.

1990-91:

Vitamin and Mineral Supplement Poisoning

I had noticed when talking to fanciers

that many used a great variety of mineral and vitamin supplements and it was not

unusual for 2, 3, or even more of these to be used in one stud.

1990-91:

Clagged Vents

In 1990-1 it was decided that we would

investigate the condition of clagged vents in which large amounts of droppings

accumulate around the vent.

1991-92:

Eye Diseases

The last project, undertaken in 1991-2,

was an investigation of eye problems in budgerigars.

Also in 1990-91 the

University purchased some very expensive equipment for doing blood chemistry on

the normal domestic species that we deal with and this had the capability to do

chemistry on minute amounts of blood. This equipment was used to find out the

normal levels of a number of substances in normal budgerigar blood and,

following this, to use it as a method for locating the problem in sick birds. It

has proved its worth in the diagnosis of liver and kidney diseases and also in

cases of diabetes.

Conclusion

Due to the lack of

support by the fancy for the last 2 projects, and also as we could not think of

projects which would appeal and be practical for 1992-3 at least we were

offering a free treatment and advisory service to members of the LCNWBS; other

fanciers are to use this service but a charge was made for any work done.

While the above

describes briefly some of the "official" projects, a lot of other work has also

been carried out. Quite early on in the project it became clear that there was a

need for a diagnostic service using samples, live birds or post-mortem

examinations and at least as much time has been spent on this as on the

"official" research. Many interesting diseases have been seen and even now new

ones are cropping up. Small projects have been carried out on three of the most

serious diseases; psittacosis, budgerigar fledgling disease and

megabacteriosis.

In brief

psittacosis is treatable and there is certainly no need for fanciers to put down

infected studs. The other two diseases are not currently treatable but we now

know enough about them to advise as to what to do and what to expect.

There have been

other benefits to come out of the project. The first of these is that the

veterinary students at Liverpool University now get some lectures on budgerigar

diseases and a certain amount of hands-on experience. Second we are now able to

offer to veterinary surgeons in practice, an advisory service for budgerigar

problems and this is quite popular. Third, it became obvious very early in

project that fanciers were having difficulty in locating vets with experience of

cage birds and their diseases. As a result of this a list was drawn up of vets

working in this field, and it has proved very popular indeed and has now been

amalgamated with one produced by a commercial company (Vetrepharm) so that

fanciers should always be able to find somebody in their area who can assist

with problems.

Last but not least

there is no point in doing this type of research and clinical work unless the

findings are made available to the fancy and I am most grateful to Cage and

Aviary Birds, The Budgerigar and the News Report of the LCNWBS for publishing

articles based on the work I have done; articles are also published in various

veterinary magazines from time to time to keep the profession aware of what has

been going on.

While the

"official" projects have been stopped, for a year in the first instance, I do

very much hope that the mutual assistance which has been of such benefit to all

parties, the fancy, the research committee, and myself will continue and

flourish for many years to come.

Original text

Copyright © 1992, Dr John R Baker.

Medical Conditions and Diseases of the

Budgerigar

Budgerigar:

Melopsittacus undulatus

Budgies and

cockatiels are the most common pet birds seen in practice. It is important to

understand the most commonly encountered diseases and conditions of these

popular little birds, in order to be able to properly diagnose and treat them.

When dealing with the owners of budgies and cockatiels, do not underestimate

their attachment to these little birds. Offer them the same diagnostics and

level of care that you would the owner of a macaw or Amazon parrot. To many

budgie and 'tiel owners, their birds are true members of the family and they are

willing to have any necessary diagnostics performed, and have any required

treatments administered. Do not compromise the quality of care offered to the

smaller birds.

The budgerigar,

Melopsittacus undulatus, is a fascinating little psittacine with

well-deserved popularity due to its small size and big personality. The budgie

is the best known of all parrots, and has found its way to virtually every

country in the world. It may be considered a domesticated parrot, as it has bred

prolifically in captivity since the mid 1800s. While sexual maturity usually

occurs at approximately six months of age, researchers have shown that young

male budgies may produce spermatozoa within 60 days of leaving the nest. This

rapid sexual development is a physiological adaptation to an arid environment

and enables very young birds to reproduce quickly when conditions are

propitious.

Most parrots are

taken out of the nest as babies to be hand fed to make them more tame, however,

budgies are usually left with the parents until after they are fledged. Baby

budgies tame down very quickly and make devoted, wonderful companions.

Budgie

Statistics

Budgies are about

seven inches in length and weigh between 26-30 grams. English budgies are

slightly larger and weigh proportionally more. The average life span is between

six and ten years, and the maximum recorded life span is 18 years. Budgerigars

are native to Australia, and tend to live in large flocks, although they may

also be found in small parties. In their native habitat, they feed on seeds

procured on or near the ground, and the important food items are seeds of native

grasses. Crop contents studied included grass seeds and a few seeds of

Portulaca oleracea. Budgies have been described as extremely nomadic in

Australia and they can be found inhabiting timber bordering watercourses,

sparsely timbered grasslands, dry scrublands and open plains. It is very

important to note that wild budgies are very active birds, flying great

distances to visit waterholes and seeding grasses. They fly from tree to tree

and scurry through the grass searching for seeds. Many problems with captive

budgies can be directly attributed to the sedentary lifestyle of the pet caged

budgie, when its activity level is compared to that of a wild budgie.

Male budgies can be

excellent mimics and can develop huge vocabularies. Hens may whistle and can

learn a few words, but they are not nearly as loquacious as males. Budgies are

dimorphic. Adult males of most colors, except albino and the very pale pastels,

develop a blue cere. Hens have a lilac or tan cere that turns brownish upon

maturity.

Cockatiel

Statistics

Cockatiels are

usually taken from the nest when they are two to three weeks of age for

hand-feeding. Any of the commercially available hand-feeding formulas are fine

to use. Cockatiels are usually 12.5 inches in length, and weight between 75-125

grams. Larger boned show cockatiels may weigh 10-15 grams more. Feel the

pectoral muscles, if they bulge away from the center keel bone, then the bird is

probably overweight. Sexual maturity may occur as early as six months of age,

and up to 12 months. The recorded maximum life span is 32 years, but on the

average, a cockatiel will live for 15-20 years in captivity, given proper

conditions.

Cockatiels are

dimorphic once they have molted out the baby feathers. This molt usually occurs

at about six months of age. Adult grey males have bright yellow facial feathers

and bright orange cheek patches. Adult grey hens have dull facial feathers. With

the color mutations, adult males have solid primary remiges and retrices. Hens

will have yellow dots on the remiges, stripes of yellow on the retrices. These

marks are subtle. Males are great mimics, and can whistle tunes and talk very

well. Hens will vocalize, and can whistle a bit, but most won't talk.

Nutritional

Disorders

Budgies and

cockatiels consume a primarily seed diet in the wild, and they do seem to thrive

on a seed-based diet. However, pellets, sprouted seeds, fresh fruits,

vegetables, pasta, whole wheat bread and healthy table foods are sound additions

to the budgie diet. A budgie that eats just seeds should have access to a

cuttlebone or mineral block, and should receive supplemental vitamins (but NOT

in the drinking water) as directed by your avian veterinarian. Some budgies and

cockatiels are extremely resistant to dietary changes.

It should be noted

that it can be dangerous to try and convert any bird to a different diet without

first ascertaining that it is healthy. Dietary conversion in a sub-clinically

ill bird can precipitate a health crisis. Always evaluate a bird's health before

to attempting to change a budgie's or cockatiel's diet to make sure that is

healthy enough to withstand the stress of changing the diet.

Budgies, and to a

lesser extent, cockatiels, are very prone to obesity and the problems related to

being overweight. The obese budgie or cockatiel may develop lipomas, which are

benign (non-malignant) fatty tumors. These may be found over the crop area, the

chest or the abdomen, most commonly. In other cases, the bird may develop

generalized lipomatosis, which is a layer of fat over the entire surface of the

body under the skin. Xanthomas, yellow fatty tumors, may also occur. Surgery may

be necessary, especially if the skin over the tumor ulcerates, but often, the

tumor will recur, unless changes are made in the diet and activity level.

Obese birds usually

have some degree of liver problems. When fat is deposited in the liver, normal